Rivalry Last Evening...

....This evening the competition was lively and severe.Because as third and last appeared Alexei Sultanov.a great favorite of the crowd of diligent listeners.who already in the previous stages more than once conquered the audience with his glittering virtuosity .Likewise now,he started Fantasy on Polish Themes in the climate of reflective meditation.but which later through more stormy episodes reached vivacious and showy finale,maintaining exemplary rhythmic discipline.However.in the Piano Concerto in F minor he presented the performance of really great dimension.imposing with technical ease.leading continuos flow of musical narration.and beautifully interlacing it's dramatic and poetic streams,and in the finale also with it's dancing elementOne could see.that performing with an orchestra not only does not quail him,or strain him.but gives him sincere joy .If only his youthful temper would not carry him to far...Though,this indeed,seems to cause spontaneous ovations from the audience.

J.Kanski

Trybuna,October20,1996

First Sensations

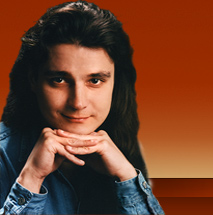

13-th Chopin Piano Competition/Third Day. This sensation has already been expected: 26 year old Alexei Sultanov born in T

Dorota Szwarcman

Gazeta Wyborocza,October 5,1995

There is a Favoritel

The audience has already chosen its favourite. He is Alexei Sultanov who represents

from Express Wieczorny, October 4, 1995

Virtuoso pianist captivates audience

Challenging, sensitive performance features works of Frederic Chopin. From the beginning to the end the audience was spellbound by the piano performance of Alexei Sultanov at Friday evening's concert in the Rushmore Plaza Civic Center Theater. Sultanov, winner of the Van Cliburn International Competition in 1989, has performed throughout the world. Since winning, he has performed in more than 100 concerto and recital performances in the major music centers of the world, including

The all-Chopin concert included, among others, the "Ballade in F minor," the "Nocturne in С minor," the familiar "Waltz in E b major," the "Sonata in В minor," and one of his best-known works the "Polanaise in F minor." Technically, Sultanov knows no limits, His, control is awesome and the speed with which he executes the most difficult challenges is inspiring. However, he is also capable of the) most refined and sensitive performance of the slow and sustained sections of the music. For example, in the slow section of the " Sonata" he brings all the depth of the emotional content of the music to the audience bу his controlled performance. Sultanov is without a doubt one of the shining stars in the new generation of virtuosi pianists. He has a formidable technique, great power, is a master of the rubato as applied to Chopin, and understands and makes use of the value and the power of contrast needed in the performance of the romantic music of Chopin. The program was well attended by many young people who, I suspect, are studying piano. The performance must be an inspiration, not only to the adults, but to these youngsters.

The Rapid City Concert Association is to be commended for ' making it possible for the citizens of the community to have the opportunity to see and hear this example of high-quality musicianship.

By Victor Weidensee Journal Reviewer.

How Chopin Was Played In

Because Chopin is Unperformable

Chopin is almost unperformable. He is so difficult, that to bring all essence, all important features and all details signalized in the notes is beyond the capabilities even of a great pianist. Chopin is almost unperformable, because his music is diabolically dense, condensed and charged with musical substance. In it, there is neither empty nor mechanical virtuoso's moments. In Liszt's etudes or even Beethoven's sonatas, the pianist can allow himself a moment of intellectual and emotional rest, when only his fingers are playing, and the mind is resting. In Chopin's compositions, the pianist cannot allow himself even a second of rest. His mind has to follow each sound even in the fastest passage, and even in the most conventional ornament. If he would not do it, we perceive immediately his performance as violating this music, out of style, a

And Here Comes the Jury

But for the jurors, it does not matter whether the pianist plays in a new way, but whether he plays Chopin in the Chopin way. And "the pure Chopin style" is - in jurors mind - performance more or less corresponding to the aesthetic principles of the so called

Then the years pass by. The recordings of our wronged-by-the-jury favorites reach us and, with some surprise, we are discovering that we almost do not understand why we were so taken over. Chopin is difficult, almost unperformable.

One who follows the public favorites of the competitions, knows that none of them has become the great Chopin pianist, and even making the stunning career Ivo Pogorelich now plays Chopin in manneristic way. which is simply difficult to bear.

But With Sultanov It Could Be Otherwise

But Sultanov has not fascinated the audience because he is an individualist. Each competition is full of individualists and that in the long nin brings little to the Chopin music. Sultanov has not fascinated the audience because he is a titan of the piano cither. The

What Has The Audience Been Reminded Of By Sultanov?

He reminded firstly, that Chopin can be played lightly - that in Chopin music there arc indeed thunders, but the best way of their performance is to prepare a background for them by light, effortless playing. A thunder which thunders in a jet is not a thunder. For a thunder to sound like a thunder, it needs to be proceeded and followed by silence For the pianists of the older periods that was a primer. A Chopin pianist, who played light, even a little (as for requirements of a large concert hall) too light, was able - as noted by contemporaries -to draw out sounds of extraordinary power. But he did it only for few seconds. Jozef Hofmann usually proceeded the same way. He played the Polonaise in E-flal major (that with Andante spianato) from the beginning to the end with the lightness of waltz, from which only even' so often arose a part of melodious cantillena or a powerful thunder of the storm. Sultanov did not allow himself to be dumbfounded by the teachers' standards of making a noise in Chopin music, and returned (in Scherzo B-flat minor, in etudes, in waltz) to the tradition of the great masters of the past, to the tradition of Chopin virtuoso himself and that was revealing.

He reminded secondly, that Chopin docs not need to be continuously blurred with the pedal - because playing it light, dry without the pedal brings into prominence, in the best way, the precision and elegance of Chopin's music. The old masters knew it perfectly. But -exactly - they were lo be sure masters. Blurring with the pedal allows usually to hide technical imperfections of a performer. Sultanov docs not have anything to hide.

He reminded thirdly, that the music is a kind of pleasure, and not a form of torture. That playing music has a sense only when it brings joy, that Chopin at the piano was rather a jester not a sullen man and that in his music, besides sorrows and ecstasies, there arc plenty of various forms of joy. humor and wit. When he (Sultanov) played the Waltz in E-flal major, the hall turned silent in surprise, and then it burst with applause. Something like that, to crack jokes of Chopin, that the Chopin competitions have not yet seen. Competitions have not seen it, because the "

How Sultanov Revived The Music

In the period of J. S. Bach, in the period of Haydn and Mozart, in the period of Chopin, there was only live music, only one live music. A composer was then simultaneously a performer. A performer was then at the same time an improvisator. In the 20th Century the live flow of music divided into two further and further separating and drying streams - the stream of creation, and the stream of performance. The institution of a pianist, or of an officer for fingering, appeared who was not a musician. Even in the recent years, the extreme case emerged - of a pianist who does not perform in front of an audience, but who records, records, records. Listening nowadays to drafty composers and equally drafty performers, one can have an impression that today the only live sphere of music, the sphere in which playing becomes an act of creation, is jazz. Sultanov raving at the piano in the style of old masters and cracking jokes of Chopin, reminded us, that the piano performances were once a live art. Perhaps Sultanov playing really improvises, or perhaps he only pretends to improvise. But he who can pretend so well, is a master.

No first prize was given at this year's 13th Chopin competition.The pianists weren't the only ones who felt cheated.

The news was not taken well.

For the second time in a row, the jury has not granted a first prize to any participants in the Frederic Chopin International Piano Competition. Awards for the best performance of a Chopin Polonaise, Mazurka or Concerto were also deemed too good for the finalists. At last Friday's awards ceremony and gala winners' concert in the National Philharmonic, jury chairman Jan Ekier defended the decision by saying, "The Chopin tradition has certain standards which must be upheld."

The question on everyone's mind is, however, which" tradition is Ekier talking about?

Celebrated senior music critic of the The New York Times and jury member Harold Schoenberg was perplexed by Ekier's statement. "If Ekier wishes to uphold the Chopin tradition, then he must clarify as to which one he is referring to. Is it Paderewski's version, or is it Hofman's, Friedman's or Rosenthal's? All were Poles and all had differing opinions as to the correct interpretation of Chopin's music. This esthetic question, above all else, needs to be addressed."

This is not the first time a jury has decided not to grant a first prize. In the last competition, which was held in 1990, the jury was of the opinion that the competitors were not good enough for the title. They believed the level was not indicative of the Chopin crown—which boasts such luminary former prize-winners as Maurizio Pollini, Marta Argerich and Krystian Zimerman.

Apparently, the jury of this year's competition ' had the same opinion. And, as a result, they (perhaps unwittingly) have established an unwritten law which will continue to affect the competition: If the competitors cannot conform to the jury's biased notions of what constitutes a "proper" interpretation of Chopin, then they should not be vexed by the absence of a first prize.

The results (or lack thereof) were announced the evening before the gala closing concert. Upon hearing the results, one performer felt no need to play again before the jury if they didn't credit him with enough talent to win. So on Friday night, much to the disappointment of those present, audience favorite and amazing Russian virtuoso Aleksei Sultanov (who shared second prize with Frenchman Phillipe Giusiano), did not appear out of protest. In a letter written to the press, Sultanov expressed his regrets, "I am sorry that I am not there tonight. I will be back very soon to play for my beloved people of

from Gazeta Polska.

by Piotr Wierzbicki

English translation by Bogdan Krasnowski