|

|

Sultanov's triumph 19-year-old Soviet wins Cliburn gold with fire, brilliance By Barry Shlachter

Fort Worth Star-Telegram

When it came down to a decision, the jury found a rousing and individualistic player who did communicate with the audience, conferring last night on 19-year-old Soviet Aleksei Sultanov, the youngest of the original 38 hopefuls, the gold medal of the Eighth Van Cliburn Piano Competition. After the silver was announced, the message was clear to Sultanov, sitting in the middle of the Fort Worth-Tarrant County Convention Center, sandwiched by Soviet colleagues. He threw his bushy head back against the top of his seat and let out a deep breath. When his name was then called out as the winner, the short and wiry pianist leaped to his feet, raised both hands in the air and closed each into a triumphant fist, reminiscent of the knockout scene from Rocky. "Sultanov looks like an angel, plays like a devil and is full of wonderful, ordinary human feeling," said one member of the audience, |

The waifish pianist from the Central Asian city of Tashkent, who listens to rock and jazz in his leisure, practices the martial art of kung fu and is not afraid to handle cobras, also stood out with his commandeering of the keyboard.

"The guy is powerful," said juror Lawrence Leighton Smith, music director and conductor of

"I think he has instant dynamic appeal (and) tremendous talent, " said juror John Lill. winner of the 1970 Tchaikovsky Competition.

The 30-year-old Cocarelli, noted for his unemotional but masterful performances of Brahms, maintained his almost neutral tone.

Asked how it felt to lose to a pianist from a younger generation, he looked around the backstage area packed with cameras, reporters and fans, and cither couldn't or wouldn't answer directly. He said the question was "too delicate." The stiff, introspective Brazilian said the Giburn was his last competition.

The bronze went to Italian Benedetto Lupo,

He will devote himself to concerts. His next appearance will be at an acoustically perfect Greek Orthodox church in

Juror Sergei Dorensky of the

If there was any major upset, according to some close Cliburn watchers, it was the relatively low ranking of Soviet Alexander Shtarkman who had been on many listener's lists for a place among the top three. He got fourth.

|

What now? "I will try to have fun, especially after the results," said Shtarkman, whose studied, intellectual approach was often cited in contrast to Sultanov's dynamic playing. Afterward, Shtarkman handed Van Cliburn seven photographs taken of the American pianist when he won the 1958 Tchaikovsky Competition. Some included shots with Shtarkman's father, Naum. who won the bronze that year and earned Giburn's respect. The Texan kissed Shtarkman on both checks, Russian-style, then told him of a moving competition performance by the young Soviet's father "I remember his Chopin. It was just to die." - Shtarkman, in halting finglish that gave his words greater sincerity, replied: "I am happy to meet you. You are to me like a legend." Giina's Tian Ying, who lives in Jurors said the voting, which took two hours for all categories, went relatively easily. |

"If he is exploited too much and too soon, of course it's going to be a bad thing," Lill said. "The quality of anyone can suffer if quantity takes over. He's got to pace himself. He's a great talent."

At his news conference, the 5-fcot-4 pianist of Russian-Uzbek parentage responded to the question of whether he was ready for the rigors of the numerous concert dates that come with the Giburn gold.

"If you have too many concerts, it can go two ways," he said through an interpreter. "It can bring you harm or it can help you. ... But there's one way to fulfill the (challenge). It's practice, practice, practice."

Looking flushed from champagne toast, an exuberantly self-confident Sultanov confided, "In this competition, I wanted the first prize or nothing."

Jury' chairman John Giordano, conductor of the Fort Worth Symphony, broke his silence on individual competitors after the awards were distributed, disclosing that even before the contest, he instinctively felt that Sultanov would be among the three medalists.

"His incredible energy and talent came through in the screening," he said of the auditioning session videotaped in

Piano competition have been attacked by critics as producing relatively few great artists, choosing instead the common denominator — every' juror's second choice.

Richard Rodzinski, the Cliburn's executive director, had made numerous public assurances that the jury this time would select 3 winner who could communicate with audiences, if not excite them.

"A lot of complaints have been made about contest winners — and they've all been true," said juror Abbey Simon, a noted concert pianist and recording artist. "They all sound alike, bland.

"But with Mr. Sultanov. we have a fearless, independent player who can be criticized in all sorts of ways, but we all can be criticized. If you arc looking for a pianist with charisma, a pianist who is brilliant, I think Mr. Sultanov with his wonderfully poetic gifts fills the bill beautifully."

The American juror dismissed contentions that awarding a pianist so young might prove professionally damaging.

"He'll have to sink or swim," Simon said. "I think Mr. Sultanov is the kind of person who can meet the repertoire demands and grow in a formidable way. But his growth is his own responsibility.

"And if he is as intelligent and'gifted as I think he is. he should be able to meet all

the challenges I'm sure he's an original.

I have a feeling his teachers find him difficult — but he's a delight to hear."

Brazilian Cristina Ortiz, who won the Cliburn in 1969. also at the age of 19, cautioned that gold medals do just so much for pianists, no matter their maturity.

"It's all up to them now," she said. "The ones that have it in them will make it whether they have the top prize or not. It accelerates the process (of building a professional career). It may not mean much.''

Who's No. 1 ?

Cliburn competitors face the luck of the draw

BY Barry Shlachter

Fort Worth Star-Telegram

No. 1 was the loneliest number in the random drawing last night to choose the order of performers at the sellout Eighth Van Cliburrn International Competition. No one said they wanted to go first when the preliminary round begins tomorrow morning.

"I don't mind any, but I don't want the first number," said Lora Dimitrova of

Those first up find two obstacles, explained competition veteran Victor Sangiorgio,

Even the youngest Cliburn contestant. 19-year-old Aleksei Sultanov knew better than to hope for No.

As competitors were called up in alphabetical order, hoped-for middle numbers were going left and right at a Park Hill backyard dinner party held for the occasion.

|

"I wonder when lucky No. 1 is chosen?" asked Fort Worth Symphony conductor John Giordano, who was handling the lottery. Then he summoned American David Buechner. who had the almost equal misfortune of choosing the last spot. No. 36, at the 1985 Cliburn and was eliminated early on."It's gone!" shouted a relieved Predrag Muzijcvic of Yugoslavia as the secretive Buechner took No. I, then slipped away from the gathering — as he did before a morning news conference — without comment. Giordano said the 29-year-old New Yorker showed absolutely no reaction. "Placid." was his description. But Giordano, who is the jury chairman for the two-week competition, downplayed the importance of ending up first tomorrow morning "That's why we schedule everybody twice," he said. Unlike many competitions, the Cliburn has a preliminary round with two phases in case a pianist hasa cold or a case of nerves. The musicians, most veterans of international competitions, spoke easily with reporters, playfully voicing complaints about the weather and later raising some serious problems they have with juries, repertoires and politics. |

"I don't like to come to competitions they make me nervous." Disclosed Seizo Azuma, 26, who admits to being unusually frank and even sardonic for his nationality. ("When 1 enter

Azuma, like most budding pianists, would rather perform at a recital than in a competition. Luckily for him, he already was familiar with the four-hour Cliburn repertoire, with the exception of the William Schuman work specially commissioned for the May 27-June 11 event.

"Every competition has its own obligatory works that make me angry sometimes because they're not always nice the plain-spoken Azuma said.

"At the

What's his complaint this time?

"I don't have one now," said Azuma, who paused, then laughed: "But I'll find one. ... Oh yes, too many pianos to choose from." (

Hungarian Karoly Mocsari, 26, who lives in

"They should give first prizes to everybody — 38 guys," he said. "No. 1 have a better idea. Why not let everybody play through the entire program not stages. That would be the best

solution. Of course, it might take two months..."

Make no mistake, some competitions are riddled with politics, and some with corruption, the outspoken Mocsari maintained.

"The worst might be in

What makes him think they were fixed?

"There are thousands of these first-prize winners — Asians, mainly Japanese. But you never hear from them again. Why? They just aren't good."

(Yamaha rebutted the charge. "That's the first time I've heard anything like that," said Turley Higgins, Yamaha's director of

Mocsari did not spare his native

"In the Liszt-Bartok Competition, most of the time Russians used to win. They were good, usually. It's changed now. I was able to win (in 1986). But after me, the other prizes went to Russians. I knew they would be Russians— because of the past.

"But the Cliburn is a good one," Mocsari said. "If it wasn't, I wouldn't return."

|

|

Cliburn judges surprise some with selections

Fort Worth Star-Telegram June 1, 1989

Andrew Wilde stood up and walked briskly out of Ed Landreth Auditorium, before the rest of the audience had budged. In the lobby, he paced back and forth. When someone reached out to console him, he drew away, a distant, bewildered look on his face. He had lost Kevin Kenner buttoned the jacket of hisdaik blue suit as he stepped onto the stage, his face a mask even though he had just been named a semifinalist in the Van Gliburn International Piano Competition. The names of the fortunate 12 had been announced in the approximate order in which they had played during Ave days of preliminaries. "I was waiting for (Leonid) Kuzman to be called. Suddenly my name came up," And Kevin Kenner had won. The 38 who began the competition and more than 400 avid concertgoers had waited nearly three hours to hear the jurors' verdict. It was 12:39 a.m. when jury chairman John Giordano began naming those who will play on. Among the 26 who will not. there were tears, condolences — and cynical jokes that the jurors' computer must have had a short circuit. |

Among the 12 who will, there was pleasure, and relief, and a fair amount of shock that the list of winners omitted so many who had been such favorites of the audience and the critics. Some found victory bittersweet. Inc semifinalists include three Soviets (Elisso Bolkvadze, Alexander Shtarkman, Alcksei Sultanov) and two Chinese (Lin Hai, Ying Tian). plus Jean- Efflam Bavouzet of France, Pedro Burmester of Portugal, Angela Chengof Canada, Jose Carlos Cocarelli of Brazil, Benedetto Lupo of Italy, Kayo Miki of Japan and Kenner, of Baltimore, the (one American.

The eliminated include Wilde, Kuzmin and Halim. Ju Hee Suh of

Suh, who played with an injured pinkie and won the audience said "it's OK." She filed out of the auditorium immediately after the announcement.

"It's funny." said Mocsari, "just funny ... just strange."

"It'smore acts of omission than commission "said spectator Grcgor Alien, winner of Td Aviv's Rubinstein Competition in 1980. "There were some that I thought were absolute shoo-ins — Duis and Mocsari.

Afterward, outside and surrounded by supporters, Duis still had his trademark smile.

"They may be right, what can I say," he said. "We have gone through this before, so life goes on. So if we commit suicide because of what the jury says, we'd be in terrible shape"

"Maybe I'll go to

"I'm not too coherent this early in the morning.... What's happened to some of these people? Where's Thomas Duis? I here were some excellent pianists who didn't get i n. We're not belle than them. The jury just preferred these twelve The idea —of narrowing down the 'best twelve." Pianist Andrea Nemecz the wife of semifinalist Bavouzet was too upset to accept congratulations.

"This is very much not my list," she complained. "I could tell you major, major pianists who did not get it.

"All competitions arc cruel. It's a big joy tainted with disappointments. I hope those who should have been there get enough exposure to know they are really very, very good."

"It's like an auto race," said Burmester, who made a point of shaking hands with each of the other semifinalists on stage with him. "But I've been a loser before, and most of the people up here have been losers.

"You either judge a moment or an artist. This is a moment in my life, a good moment. The others out there will have perhaps moments better than this. But right now. it is sad for them."

He wore tight designer jeans and an earring — a gold cross — and he said that the agonizing wail for the semifinal announcement "made me feel mortal."

The ceremony had taken a laborious .50 minutes, with words from contest namesake Van Cliburn and Radio Shack president Bemic Appel and gifts (Si00 from Cliburn. a portable CD player from Appel) for all 38 competitors, one by one. As for Irish pianist Hugh linney. he's calling it quits for competitions. "I decided that before it began. So frequently first rounds of any big competition produce some strange results, On the whole, I said what I wanted to say up there on stage (playing the piano)."

American John Nauman's had enough, too. "This might be it for competitions. I will go on though . He was red-eyed. "Look at that group." he said, pointing at the 12 semifinalists posing for a photo around the Steinway. "l'd kill... No, I wouldn't kill... "But for eight months, this was all I did...."

On stage, with his teacher Zhou Guang-Ren translating, semifinalist Lin was saying. "I feel very happy, but in

In the lobby, someone else was trying to console Wilde, who had won bravos for his playing and his sparkle.

"Yes, you are surprised ... " he murmered. He recited it, as if he were trying to make sense of it, and he walked off toward the side door, with his wife Maria following.

His friend from

Van Cliburn demands the pianist's best

By Carl Cunningham

Post performing art critics

FORT WORTH - Every four years, there are 16 days in May and June when this city becomes one of the music capitals of the world — at least where the world of piano playing is concerned.

This year, the attention is focused on 38 young pianists, aged 18-31 who were the competitors chosen for the eighth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. They are the lucky ones to reach for sudden stardom in one of the world's most grueling, heavily publicized piano competitions.

In the 27 years since it began, this competition has become a sort of standard-bearer for international musk competitions, applying the latest wrinkles in technology, business and marketing techniques — and cash — to the venerable but mysterious ritual of choosing a winner.

On the stage "of the competition, six pianists try to outdo each other and be the single one to stand on the winner's stage.

They sweat and smile nervously between pieces, as tension fills the auditorium at

But there's another question whispered seat-to-seat. "Where is Van Cliburn?''

The 54-year-old pianist and namesake of the quadrennial piano competition is a mystery man. Van Cliburn has taken on that aura in the world of classical musk since, at the age of 23 he stunned the world by winning the prestigious International Tchaikovsky Competition in the

Cliburn says he sees the competition's jury process, which winnows a field of 38 competitors down to six finalists, then a winner, as "a way of divining an opportunity cycle" for young artists.

The competitors' careers, he believes, will hinge on their ability to communicate music, what he calls "great pages of literature," to the audience and. during the competition, to the jurors.

"This is a performer's competition, and a performer is a servant; he serve» the composer and he serves the audience." Cliburn said.

"In my own case, I'm a very good audience — I always say that I am — because I go to hear someone because I enjoy being a member of an audience and 1 get very excited if someone speaks to me."

« Cliburn makes no choices in his own mind as he listens to the performers. Instead envisioning each in his or her career.

Audience members were again standing after the final recital of (he semifinals by Benedetto Lupo of

Finalists also include Elisso Bolkvadze, 22, and Alexander Shtarkman. 22. both of the

With a budget of more than $2.5 million, the

Other competitions have a more hallowed reputation in the musk world.

|

Audience members were again standing after the final recital of (he semifinals by Benedetto Lupo of Finalists also include Elisso Bolkvadze, 22, and Alexander Shtarkman. 22. both of the With a budget of more than $2.5 million, the Other competitions have a more hallowed reputation in the musk world. |

It's a moot question whether the winner is ready for the punishing performance schedule and the harsh criticism that are probable byproducts of winning the Van Cliburn competition.

Past winners have groaned under the weight of that post-competition schedule, and Rodzinski explains that the list of engagements only involves agreements in principle with sponsoring organizations. If the winner lacks sufficient performing experience, it is trimmed down to meet his or her professional readiness.

But the rules of the Van Cliburn competition are designed to weed out all but the hardiest candidates before they get to

This competition is also highly praised by the contestants for the hospitality extended by

"I must say. I think it's one of the heaviest schedules of any competition." said 28-year old French pianist Jean-Effiam Bavouzet. who was eliminated after the preliminary round of two 25-minute solo recitals.

"One of the good things about the Van Cliburn competition is that you can show many things. You can show endurance, because you have to play two concertos (in the final round), with only one rehearsal.

"And each contestant gets to play two solo recitals before facing elimination in the first round." Bavouzet noted. Many contests eliminate competitions after one recital, where they may have been nervous and not shown their best playing.

Bavouzet also liked the fact that semifinalists get an opportunity to show their abilities in chamber music, and he had high praise for friendliness and adaptability of the Tokyo String Quartet, which was engaged to accompany each of the 12 semifinalists in one of four piano quintets by Brahms, Schumann, Dvorak or Franck.

The Van Cliburn competition has also pioneered the much-praised practice of auditioning its 193 qualified applicants by the use of videotaped recitals before live audiences in 16 Asian, American and European cities, from

In this regard, Bavouzet notes that the

Pianist Angela Cheng.

While Cheng was disappointed that she didn't win. she wasn't devastated.

"It's wonderful exposure." she said, "but it's not the beginning of something — or the end of a career." Next week, she will be playing a Haydn concerto with the St. Louis Symphony.

Bavouzet was similarly philosophical, praising the exposure and the challenge of making each contestant try to exceed their previous level of achievement.

"If you can't endure it, it's not the competition (or you," he says. "But there is definitely a kind of sportsmanlike thinking about it. You have to put your highest level higher. You have to play better than your best."

Bavouzet decided to enter The Van Cliburn competition a year ago. He videotaped his audition in

The logistics of getting the con testants from dozens of foreign countries comfortably located in

Since this year's 38 competitors included pianists from

The only required party is the one where they draw lots for their order in the lineup the night before (he competition begins. Van Cliburn also hosts a consolation party for (he losers after the early rounds. And when the semifinals are over, the Van Cliburn Foundation hosts a brunch where the losers get to talk with the judges, to find out what went wrong in their performances.

Prior to that time, contestants are strictly forbidden to speak to the 15-member jury, whose 1989 judges include

Are Van Cliburn contestants disqualified if they play a wrong note or have a memory slip? Absolutely not, says Giordano, who has been the non-voting jury chairman since the 1973 competition.

"We all have memory slips and pianists grab whole handfuls of wrong notes during their regular careers," Giordano says. "What the jury is listening for are those much more important matters of style technique and interpretation."

The Associated Press also contributed to this report.

Last measure

Cliburn finalists named amid tears of joy, pain

By James Vincent Brady

Fort Worth Star Telegram

A tear came with the very first name. In a minute, Marina Mytareva was up on stage, watching the cameras flash on her charges: Elisso Bolkvadze, Alexander Shtarkman, Aleksei Sultanov. The young Soviet men had established themselves early in the Eighth Van Gibum International Piano Competition. But Bolkvadze's semifinal performances had stirred a murmur in the audience. And now, with a 1:20 a.m. announcement at

"When they called Elisso first," said Mytareva, her eyes glistening, "oh, I was crying!" . Officially, Mytareva is their interpreter, but now she felt almost maternal. "It's like three grown kids," she gushed. Jose Carlos Cocarelli, a Brazilian living in

John Giordano, chairman of the jury, told all 12 semi finalists that they were winners. But all 12 knew that only the finalists would endure in the memory. For the other half, high hopes fell bittersweet. The last American in the running, Kevin Kenner of

"I don't have any regrets. Others felt 1 communicated. Whether I win money or medals is secondary."As the finalists climbed the stage to pose for pictures with competition namesake Van Cliburn, Lin Hai a 20-year-old from

The names had come alphabetically. Bolkvadze First. Frenchman Jean-Ef-flam Bavouzet knew right then that he had not been chosen. His face tightened and his eyes glistened, and he clapped for the others all the harder.Walking into the mild night air, he turned to his hosts, George and Betsy Pepper. "I'm sorry for you much more than for me," he said, his voice upbeat, his expressive eyebrows raised. "Oh, don't you feel sorry for us one bit," George Pepper said. His wife added, "You've given us two wonderful weeks!"

And they each put an arm around his back as they walked away. Dedicated observers — parents, teachers, family, journalists and the pianists themselves — had crowded the hall, waiting for the announcement, which came nearly 2'/i hours after the last note of the semifinals. The jury's selections this time caused nowhere '. near the stir their first cuthad. Inreducing the original field of 38 to 12semifi-nalists, they had ousted half a dozen audience favorites.

Tamas Ungar, the usually outspoken head of the TCU piano faculty, was more reticent than usual. "I thought

In its peculiar way, elimi nation wasa gift to some. I am listening now," said the rail-thin Portuguese, Pedro Burmester, embracing competition production manager Ann Murphy in an aisle. "Now I can have fun."

In the lobby, he turned to friends. Now, he announced, he could at last "be free togoTexas cowboy dancing." .Behind him stood Andrew Wilde, the Briton who had failed to make the first cut a week ago. With a wagging, pointed finger and a wry eye, Wilde barked, "And you should still practice."

"Until I am 30," Burmester said with a sweep of his coal-black hair, "I will still be in the competitions, in the race. I will not practice tomorrow, but I will practice again soon. You don't stop being a pianist." The finalists don't have a moment to consider stopping

Tired, worn from days already of practice and facing a rehearse scheduled less than eight hours later, Alexander Shtarkman, 21, the only blue-eyed Soviet in the finals, said with a smile, "What can I say?" The anticipation had been building.

"For two nights, they didn't sleep, Mytareva confided. Bolkvadze, 22, looked her best for the announcement. She wore white silk and aqua heels and blue eye shadow— and her brown eyes sparkled as she sat on the piano bench, surrounded by the other five finalists, all males.

Beaming, they posed for pictures. Sultanov, 19, leaned back against the keyboard, his arms folded low across his chest, an even smile on his face. He was still thinking business. Perhaps he would switch from the

Lupo, 25, had given each of the others a congratulatory embrace as the finalists gathered on stage. As soon as the photographers paused, he dashed offstage to call his wife of 11 months in Aquaviva delle Fonti.

It would be morning in the town of 15,000 near the Adriatic coast, about 8:30, and he wanted to reach her before she left to teach literature at the local high school.

He was too late. She had gone. "I called my family," he said. "They will call the high school." Back on stage, he chattered with Cocarelli, 30, who wanted to call

Vladimir Viardo, the 1973 gold medalist, stood at the foot of the stage, wearing a tuxedo, watching the finalists pose for pictures. Was he surprised at his countrymen's strong showing?

"We have a strong school and a good selection before they come to the competition. They go through three levels of selection. But it's unpredictable what's going to be in the finals."

Ying, 20, who seemed surprised when his name was called, has not seen his parents since he came to the

He had left

"I'm glad I've got two more opportunities to play." After awhile, Richard Rodzinski, the competition's executive director, ushered the three Soviets over to an elderly woman in the front row. She wore a black dress and clutched a black cane.

It was Rildia Bee Cliburn, Van's mother. She wanted to meet them.Bolkvadze and Sultanov gave her gentle handshakes, and Shtarkman bent at the waist, took her hand and kissed it.

Staff writers Christopher Evans, Wayne Lee Gay, Barry Shlachter and Hollace Weiner contributed to this report.

A Grand Scale

This year's Cliburn has elevated contest's stature

By Nancy Kruh

Staff writer of The Dallas Morning New

But no matter which of the six finalists' names is called, the success of this eighth competition has already been assured.

Every performance has been a sellout. The level of talent, say jurors and critics, has never been higher.

And the profile of the Cliburn

is also on the rise. More than 150 reporters from around the world flocked to Fort Worth to cover the event, including representatives from the London Times, Voice of America, all three American television networks, and even the usually lowbrow Entertainment Tonight.

The attention is evidence of the Cliburn's clout in the realm of classical music.

"I think this and the Tchaikovsky (the

But with that clout comes pressures — all of which must be contended with by Cliburn organizers and competitors.

The purpose of the event has always been to recognize emerging talent in classical pianism. Yet the fact remains, 27 years since its inception, the quadrennial contest has yet to produce a bona fide superstar.

|

Teen pianist's boldness sets competition on its ear By Olin Chism Of The Times Herald Staff The naming of the bronze, silver and gold winners brought many of the 3,054 at the Tarrant County Convention Center Theater to their feet as wild applause erupted and shouts of "Bravo!" were sustained throughout the awards presentations. The selection of Sultanov virtually guarantees an interesting, if controversial gold medalist. |

His playing through the four phases of the two-week competition tended to draw strong reactions, both positive and negative. The judges thus avoided a typical charge: That competition juries generally compromise on "safe" winners to avoid controversy. At

After the awards announcement the six finalists played a series of encores. Sultanov played two.

Sultanov, a reputed black belt in karate, calmed down after making a bad impression at the beginning of the competition with his aggressive style.

He became the favorite during the semifinal round, bringing the audience to its feet during a performance of Chopin's Sonata No.

Elisso Bolkvadze of the

Lupo won $7,500, a recording session and tours. Fourth through sixth prizes were $5,000, $3,500 and $2,000, respectively. Cocarelli, Shtarkman, Kevin Kenner of the

|

|

The

Meeting with the Master

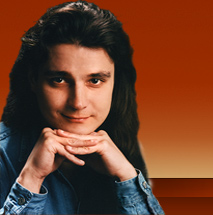

Van Cliburn is joined by the Cliburn piano competition finalists: (from left) Benedetto Lupo, Jose Carlos Cocarelli, Elisso Bolkvadze, Alexander Shtarkman, YingTian and Aleksei Sultanov. It hasn't been easy to spot Aleksei Sultanov among the Clibum contestants, because he usually is obscured by others flocking around him. He's small to begin .with; indeed, he's as small as he is young — and he's the youngest of the 38 competitors, having not yet reached 20.

But there he is, in the vortex of aspirants for a Cliburn medal, and there has been lively speculation that he may win one. Soothsayers proclaim that "this is

A neutral, non-Russian competitor says "Alcksci's problem may be getting into the finals. But if he gets that far, the judges will (hear him play RachmaninofPs second concerto and may decide he just has to have the gold medal."

Sultanov gets to play Rachmaninoff today, as well. He'll deliver the Etude No.

A Soviet Pianist, Aleksei Sultanov, Wins Cliburn Prize

By Bernard Holland

Special for New York Times

Second prize went to Jose Cocarelli aged 30. from

Mr. Sultanov's victory might be described as a triumph of brawn over sophistication. He has played the standard repertory over the past few weeks of competing with great power, unimpeachable technique and a minimum of subtlety. With this victory, he is suddenly thrust into a busy concert career, and it remains to be seen, given his extreme youth, whether Mr. Sultanov's new life will permit his musical understanding to stretch or else Impede Its growth. The talent Is certainly there.

Conventional Wisdom Upheld

Mr. Cocarelli's good showing seems to demonstrate the conventional competition wisdom that that well-groomed competence has n way of steering its way through the possible strong likes and dislikes of Jurors. Mr. Lupo's elegant technique had a similar steadiness. Perhaps the two most interesting musical personalities — Aleksandr Shtarkman. 22, of the

|

|

The winners — announced from the stage of the Tarrant County Convention Center Theater early this evening — were chosen from six finalists. Since the last rounds of this competition began here In downtown An Unexpected Hamper The finals gave all six contestants a chance to perform on a grander scale than during the earlier rounds. This was not always to their benefit or to the competition's. Most troublesome was the poor quality of playing by the |

The orchestra's execution tightened considerably on Saturday night. In the Rachmaninoff C-minor Concerto with Mr. Lupo, the horn solos went well and blendings were smoother and better tuned; but Mr. Lupo's attempts at interesting tempo fluctuations in the first movement here were largely ignored.

Lack of rehearsal time or the presence of a guest conductor (the experienced and highly professional Mr. Skrowaczewski) cannot fully explain away these performances, and it has to be asked whether the Cliburn can really be the event it largely deserves

to be with the kind of orchestra playing heard during the first two evenings of the finals.

Moving the competition from Texas Christian University's Landreth Auditorium — a reasonably intimate and acceptably resonant space where the earlier rounds were held — to a hall notable mainly for its drab, faceless modernity and poor acoustics has also not helped this event. That two of the three Soviet players momentarily lost their places during Thursday's and Friday's performances is attributable in part to nerves and pressure, though the inability to hear properly and to respond to their collaborators on stage might have contributed.

Mr. Sultanov avoided such problems on Friday by simply routing through his Chopin and Rachmaninoff pieces as if no orchestra existed, often leaving Mr. Skrowaczewski and his musicians to pant in pursuit.

The Cliburn's audience changed with the move downtown as well — from the sophisticated and near-devotional concentraters observed during the nearly two-week-long preliminary and semifinal rounds at T.C.U., to the

Shifts in the Music

Indeed, as it has grown toward its grand conclusion, the Cliburn has sometimes decreased in quality. For better or worse, it has measured its climax according to physical size — more musicians playing bigger pieces more loudly before larger audiences. It is a syndrome of inverted values that troubles the competition process in general, one whereby the more important (albeit quieter) repertory — Bach, Haydn, Mozart and the Beethoven sonatas — has been relegated to the earliest phases, while works largely of lesser quality (the endearing, inspired though roughly crafted Chopin and Rachmaninoff concertos or the Prokofiev C-major and Saint-Saens G-minor, both brilliant and comparatively shallow) have served as the final tests. Concertos, however, are for the ambitious pianist the stuff of professional success. They are the basic fuel for orchestra engagements, while recitals and their often more subtle repertory are less popular and offer less exposure. Indeed, the ambivalence between pianist as artist and pianist as career maker has been central to the decisions these 14 jurors have had to arrive at: has the Cliburn, in other words, tried to choose the best musician or has it sought out the pianist with enough strength, endurance and solidity to withstand the onslaught of opportunity which Mr. Sultanov must now face.

Extensive News Coverage

The Cliburn is a big and expensive enterprise and it depends on public exposure to prosper if not survive. Roughly 80 news organizations have been covering this event, and daily television cameras have been thrust in the faces of contestants at every allowable moment.

Yet the Cliburn's most effective promotional device is not its attraction to news organizations but its winners. It is they who go out and sell not only themselves, but also the competition that elevated them. A tacit quid pro quo is at work here, and the Cliburn is counting on Mr. Sultanov to work as hard for

In one man's opinion, a small measure of fine-tuning would make the Cliburn

World ‘s Best

By Wayne Lee Gay

It took nearly a generation of sweat, devotion, arm-twisting and love of the piano to make the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition into the

In the

The next step is obvious: to make the Cliburn into the most prestigious piano competition in the world.

Between now and 1993, the Cliburn has greater technology, greater financial backing at its disposal than any other competition. It has greater human resources at its beck and call. It has the concentrated devotion of an energetic, dynamic city.

|

|

It also faces two dangerous pitfalls: jury credibility and the management of its champions. Sour grapes arc inevitable at any competition. Losers and friends of losers arc eager to entertain and spread rumors of politics, favoritism and fudging. And if the Cliburn is not the most maligned competition in the rumor mill, it also is not the most unsullied. Its jurors have publicly questioned the fairness of decisions to which they were a party. Warranted or not» again and аgain it has been charged with considering national origin in its selection process. And it cannot afford to have another day, ever again, like the opening day of the semifinal round, when an audience of international press and visitors witnessed sub-professional performances of chamber music and the required piece. |

The obvious and necessary solution begins with the jury selection process. The competition's administration must become fanatical about the integrity and quality of its judging panel. It must listen to any and all charges of favoritism and politics, and it must go the extra mile to investigate those charges.

It must presume itself guilty until proven innocent

It must be willing to spend the money' to seek out and hire a jury whose reputation is beyond reproach, even if that means cutting back on fripperies such as a celebrity master of ceremonies.

In short, the jury at the 1993 Cliburn must be as impressive as the competitors.

The second challenge will be the management of three very different medalists. The selection of Aleksei Sultanov as gold medalist was in some ways a remarkable achievement — the Qibum actually may have given its top prize to the most exciting pianist of the generation. But he comes with some very risky attachments. He's 19. He has a lot to offer — and a lot to leam. The Cliburn must handle him and educate him. If, 10 years from now, Aleksei Sultanov is anything less than one of the most respected and beloved pianists in the world, the Cliburn will have to ask itself some very hard questions about what it is doing and why.

His career is not, as juror Abbey Simon said after the announcement, "his own responsibility." It is very much the responsibility of the Cliburn Foundation, if the Cliburn is to have credibility in the future.

Silver medalist Jose Carlos Cocarelli is a different matter. He hasn't developed the personality at age 30 to be anything other than a musician's musician. The Cliburn must shoulder a huge responsibility in developing an audience for an artist whose appeal is at best limited. If Cocarelli disappears, the Cliburn once again will have to ask itself some hard questions about its function and efficiency.

Bronze medalist Benedetto Lupo u less risky than the two ahead of him. Although his personality emerged slowly during the competition, he is an artist of staying power and consistency. The potential for disaster is much less with Lupo than with Sultanov or Cocarelli. But, if the Giburn is to become the undisputed leader on the international competition circuit, someone needs to be lying awake at night pondering how to make sure that even the bronze medalist becomes an important pianist. The moment Sunday night when young Aleksei Sultanov stood, arms raised in triumph, to accept the cheers of an audience that obviously loved him was the

It could be the golden moment when the Cliburn, basking in the international limelight, reached its pinnacle. Or it could be just the beginning for a competition that actually produces the international stars it promises.

Sultanov is winner of Cliburn

19-year-old Russian was youngest entrant

By

The l»year-old from

head — Rocky-style — and bounding to the stage with youthful exuberance.

He had every reason to be happy. The prize is one of classical music's most coveted and it virtually assures him a concert career.

The award was presented before a packed house at Fort Worth-Tarrant County Convention Center Theater. Other top finishers were Jose Carlos Cocarelli of

|

|

Critics have been saying the Cliburn needed a genuine "personality" to wear this year's gold medal, and the 14 jurors delivered with Mr. Sultanov. The diminutive Russian is the youngest of the 38 Cliburn competitors, but his explosive bravado at the keyboard ignited audiences throughout the 16 days of competition. His confidence matches his piano skills. At news conference after the awards ceremony, he explained his strategy for the Cliburn: "I wanted to get the first prize — or nothing." screened his videotaped audition in February. The two jurors sat on the committee that selected the competitors. "He's a great musician, a great artist, a real talent — unique," said Mr. Shostakovich, son of composer Dmitri Shostakovich. "I listened to three bars and I was sure he must be the gold medalist." The Cliburn victory virtually assures that. First prize includes a S1S.O0O cash prize, but more importantly, concert engagements over the next two years worth an estimated $200,000. An appearance in Despite what could be a withering performance schedule, Mr. Sultanov indicated he wants to continue his musical education at the Moscow State Conservatory, in addition to fulfilling his Cliburn obligation. I know it is difficult to fulfill," he said through an interpreter. There is only one way to fulfill it prartice practice, practice." |

Earlier, though, Cliburn Foundation executive director Richard Rodzinski explained that the tour will be tailored to the winner.

"All those prearranged concerts arc only done in principle to date," Mr. Rodzinski said before the medalists were announced. "We gear the nature of the concerts, the number of concerts and the extent of the tours toward ^heir ability. If someone is capable' of doing only 30 or 40 concerts a year, that's all we'll give them.

"What we're here to do is help these young musicians. To throw them to the wolves would be contrary to the purpose of the foundation."

All the concert agreements, he said, guarantee an appearance by one of the medalists — not necessarily the winner of the gold.

Mr. Sultanov joins Brazilian Cristina Ortiz, who sat on this year's jury, •as the youngest Cliburn winner. He studies under L.N. Naumov, who also coached 1973 Cliburn gold medalist Vladimir Viardo. After the award of ceremony, Mr. Viardo was backstage to congratulate Mr. Sultanov.

The announcement of the medalists was the climax of a ceremony over seen by actor Dudlej Moore, himself an accomplished concert pianist. After a brief intermission, each of the six finalists returned to play short selections.

Mr. Sultanov offered an unpredictable interpretation of Chopin's familiar Grande Waltz Brilliante. He came back for an encore of the composer's rousing Revolutionary Etude, pulling the audience to its feet once again.

Offstage, though, his commanding presence shrinks into boyishness: He openly idolizes Mr. Cliburn. saying the Port Worth virtuoso has a "Russian soul." He also is a student of Korean martial arts and a fan of Bruce Lee movies and jazz music. While in

|

|

Second- through sixth-place finishers also are assured significant boosts to their careers. For second place, Mr. Cocarelli receives S10,000 and a |

Sultanov’s playing isn't just at keyboard

By Hollace Weiner

Fort Worth Star-Telegram

As

"Charisma..." second-place medalist Jose Carlos Cocarelli had mused at the backstage news conference, "that's communication with a lot of love all the way through. My colleague" — he motioned toward Sultanov — "can tell you more about charisma."

|

As if he were watching Charlie Chaplin. His favorite scene, from The Gold Rush, is one in which Chaplin sticks forks into his dinner rolls, pretends they are people and performs the dance of the buns. "You don't need to speak English to understand Charlie Chaplin," said Susan Wilcox, Sultanov's host in When Sultanov arrived at the Wilcoxes' Wedgwood doorstep, he'd never heard English outside the classroom. "I think his English was good to begin with, but he was afraid to speak it because it was completely untried," said Jon Wilcox. So at first they stuck with Russian, relying on Jon's three years of the language at And Sultanov understood the meaning of a scream — like the shriek Susan emitted when she spotted two garden snakes taking a dip in her backyard pool. "He knew I hated snakes. We had talked about it," she said. Sultanov picked the snakes out of the water... and surreptitiously carried them to his hosts' bedroom. "At that point, I knew he was part of the family, because he thought that was very funny," Susan said. Sultanov was so proud of the prank that when a reporter telephoned for details, he gave his first English interview. Eagerly. |

"They were no little, no big," he said of the snakes. "Susan was very afraid, yes. I don't afraid of snakes, no."

Whatever the case, the incident endeared Sultanov to the couple, who have a cat but no children, and they began calling him their "adopted son."

They knew he was an accomplished martial artist — he has earned a black belt — but it was not until the competition that they knew the kind of pianist he was.

"He practices a few bars at a time, slowly so he can hear every note," Susan said. Then he gets on stage and rips through a piece in record time. "We never heard a full piece until the concerts."

They have, however, sat through a number of kung fu movies from beginning to end.

The party almost went on without them.

By Carol Nuckols

Fort Worth Star Telegram

It was almost 9 p.m. before the medalists, who had been detained by а news conference, arrived at the Worthington Hotel's Grand Ballroom for the party in their honor. About 1,400 guests had sat or stood around for nearly two hours, sampling roast pork, black-eyed pea relish, fried catfish, fresh berry shortcake, locally made cheeses and other upscale, down-home cuisine.

But when the medalists arrived they were met with congratulations, hugs, cameras and requests for autographs.

Cold medalist Aleksei Sultanov paused on the way into the ballroom to view- the collage that photographer Chris Reynolds has been compiling from every party. Standing beside him was 12-year-old Philip Viardo.

Inside the ballroom, Robert Gourdin, North American sales director for Moet et Chandon, decapitated four bottles of champagne with a saber to oooohs and gasps. He poured one bottle of the bubbly into the top glass of a pyramidal stack of glasses, then invited the medalists to join him in pouring the other bottles until champagne flowed like a fountain.

The first glass went to Sultanov who, it should be noted, is underage. It also should be noted that he drank i t down mostly i n one gulp

The crowd gave him a "bravo.”

|

"We are ecstatic—we picked him from the first,” said Staci. "No question that Aleksei was the best pianist here," said Steve, "The jurors were right on." . The other reason: The Eismans have one of Sultanov's piano strings — "the one be broke on the "We're getting the string framed with Aleksei's autograph,” said Staci. "We haven't met him yet, but we will" Martha Hyder pulled out all the stops for the alfresco luncheon she threw yesterday for out-of-town guests. Mariachis greeted the guests, ' kilim rugs were spread out everywhere and big bee-trimmed umbrellas shaded the fuchsia-draped tables. Jurors mingled with all the competitors for the first time since the competition began. Previously, jurors and competitors had been kept segregated, but by yesterday afternoon, it didn't matter. The decision had already been made. "I know, but I'm not telling." smirked jury chairman John Giordano. The star movie star Dudley Moore, who emeced the awards ceremony. Giordano took the opportunity to suggest a "This is my wife," Giordano introduced her. Th3t was Why? It's the punchline to a joke Giordano had been telling all week, which can't be repeated here. |

The two stood back to back Saturday night at the reception that followed the last competition performance.

The decision:

The reception, at the Fort Worth Club, resembled a Cliburn family reunion, with relatives showing up from Sheveport and beyond Also present was Gretel Ormandy, widow of conductor Eugene Ormandy, to whom Cliburn will dedicate next Monday's concert with the Philadelphia Orchestra — his first public performance in more that a decade.

As the two-week marathon of parties came to a dose, guests were congratulating entertainment chairman Mildred Fender for organ* iring the social calendar.

Things went of Twith few hitches. Only the ranch party was forced indoors by rain. The air conditioning went out at River Crest Country Club during a Saturday luncheon for jurors, but box fans were brought in and windows opened, and nobody seemed to mind

The jurors, incidentally, earned reputations as social animals. They've held up not only to the endless hours of music but also to the nonstop round of luncheons and dinners, at' which they tended to linger. And then they partied into the night at the Worthington Hotel's hospitality suite.

What's in store for Cliburn Foundation workers, now that the medals arc awarded and everyone else is winding down?

" Instead of 80-hour weeks, maybe well only be working 60." said publicist Beth Wareham, yawning frequently during a quick phone interview-. "It will be absolute chaos for us for at least two or three weeks solid”

This morning, there are meetings among the Cliburn, the medalists and international management reps. Then Sultanov must begotten to the airport in time for a 4 o'clock flight to New-York — he has an appointment tomorrow with NBC’s Today show.

After that, there are press kits to compile; travel details to arrange, a competition CD that needs to be publicized ...

Cliburn winner plays at more than piano

|

Of the six finalists, only Sultanov looked like he was having a good time at the piano. He plays power fully, teasing the audience with body language. When he bows, his long hair flops into his eyes, and you could swear you see him smirking. As if he were watching Charlie Chaplin. His favorite scene, from The Cold Rush, is one in which Chaplin sticks forks into his dinner rolls, pretends they are people and performs the dance of the buns. "You don't need to speak English to understand Charlie Chaplin," said Susan Wilcox, Sultanov's host in When Sultanov arrived at the Wilcox doorstep, he'd never heard English outside the classroom. "I think his English was good to begin with, but he was afraid to speak it because it was completely untried," Jon Wilcox said. So at first they stuck with Russian, relying on Jon Wilcox's three years of the language at |

And Sultanov understood the meaning of a scream — like the shriek Susan Wilcox emitted when she spotted two garden snakes taking a dip in her back yard pool.

"He knew I hated snakes. We had talked about it," she said.

Sultanov picked the snakes out of the water ... and surreptitiously carried them to his hosts' bedroom.

"At that point, I knew he was part of the family, because he thought that was very funny," Susan Wilcox said.

Jury earns more darts than laurels for picks

By John Ardoin

Music Critic of The

FORT WORTH — It's all over, in-eluding the shouting, at the eighth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. As had been expected, the gold medal went to a Soviet pianist — Aleksei Sultanov. At 19, he is the Cliburn's youngest winner since 1969's Cristina Ortiz of

Though Mr. Sultanov is far from a fully formed artist, he is one who leaves excitement and controversy in the wake of his playing. And that may even be what helped him win. The Cliburn sorely needed a spirited winner after the bland choices made in the past two competitions.

Nor was it difficult, personal tastes aside, to understand the awarding of second prize to

What was unfathomable was the jury's preference of

For me, this was the one sad moment of the awards ceremony, and one that seemed to go beyond mere personal preference. But, as they say, that's horse racing. However, if Mr. Shtarkman was better than fourth,

An unexpected decision was the splitting of the chamber music prize — renamed by Van Cliburn in memory of the 1977 laureate. Steven De Groote — four ways. It went to

After the awards presentation, the finalists were heard in encores. None of the playing did anyone credit, but after all the six had been through, who could blame them for the widespread feeling of letdown that had set in?

In any such event, what matters when all the prizes are given and the applause has died away is whether one can accept with good grace and firm belief the first prize winner. That presented no problem for me at any rate, in this year's Cliburn.

That virtuoso guy is so totally cool

In a Sultanov sweat: You know Aleksei? That teen-age guy living over at the Wilcoxes' house? Well, you won't believe, man. That guy won the Van Cliburn!

Ч 1 know, man. It surprised me, too. I knew he played music, but I thought, maybe he's in some Deep Blum punk band! ."

He’s only19, man. I saw him the other day. renting Bruce Lee movies at Blockbuster. He had some new

J talked to him, man. He's really cool. He loves the Wilcoxes' house, because they've got "th1sЈttur pool.

You know what he did, man? Well, one day. he finds a snake in the pool. So he, like, grabs it, and takes it inside and scares Mrs. Wilcox!

He says once he caught a cobra, man! Grabbed it in his lore hand! Cool! (Not here. In

New movie idol: Yeah, Aleksei's cool, man. He's only S-foot-4 and he doesn't even look 19. Bet they'll card him to get into PR's!

And he's real good-looking. With all this, like, hair. The Cliburn videos go on Channel 13, but he should make MTV!

It's so cool that a teen-age guy woo. Terri Allen this girl from Haltom City, agreed

"He's four days younger than me," she said. "I've earned this good-luck crystal for him all week, and I want to give it to him.

"I am just in love," she said. "I would die to hold his hand."

Katherine Blackmon and Chuck Brizins from SMU were happy, too. They're both 20.

" He’s young and spunky, and so different." Blackmon said.

"He's so excited." Brizins said. "When he won, he threw his hands up and screamed. And he held up the cup, like he'd just won

Bruins wanted Aleksei to ditch his dosing Chopin: "I thought, come on, man. Kick into little Elton John."...

Ready to play: You know what else? Aleksei just drove his first car last weekend. Mr. Wikox let him drive the

I saw Aleksei on TV, man. Everybody asked if fie can handle the pressure. Sure he can! What's a piano, after you've handled a cobra?

Anyway. Aleksei’s really cool

He knows kung fu.

Look for two Soviets, Brazilian to be winners

By John Ardoin

Music critic of the Dallas Morning News

FORT WORTH — The Van Cliburn International Piano Competition was topped off Saturday evening with concerto appearances by Brazil's Jose Carlos Cocarelll and Italy's Benedetto Lupo. Only the pry remains to be heard f rom at Sunday afternoon's awards ceremony.

This third and last stage of the Cliburn has been a difficult and perplexing time for performers and listeners alike. A few bids have been enhanced —

But there have been I no buzzes or thrills as I were experienced In the I preliminaries and the semifinals. Maybe the reason Is simply fatigue or saturation. But whether a contestant lagged behind in the finals or sprinted ahead, it is the Jury's duty to consider all phases of a pianist's playing in making its final decision. On this count. I can only fervently hope It will be responsible.

1 believe the 1989 medalists will be the Soviet Union's Alexander Shtarkman and Aleksei Sultanov and

He also was heard in Brahms' First Concerto, and It was rocklike, virtually note-perfect and quite admirable. It wasnt exciting or illuminating, but It was very professional and easily outranked Mr. I.upo's pedestrian playing of Chopin and Rachmaninoff concertos.

So where will that leave the six finalists? This is a difficult Jury to second-guess, but I expect first prize to go to Mr. Shtarkman, second to Mr. Sultanov end third to Mr. Cocarelll. However. It Is easy to formulate other scenarios.

For example, first prize might go to Mr. Sultanov and second to Mr. Shtarkman. I also could envision Mr. Sultanov and Mr. Cocarelll sharing second prize, or even the two Russians splitting first prize. I don't see Mr. Cocarelll In the running for first prize, however..,

As for the other prizes, I expect Mr. Ying to take fourth. Mr. Lupo fifth and Miss Bolkvadze sixth, although Mr. Lupo might luck out with fourth and Mr. Ying fifth. As for the chamber music award, I expect It to go to Mr. Cocarelll, and the prize for best performance of William Schumann Chester to be Mr. Shtarkman.

And, if I bad my way, I would create a special prize for Stanislaw Skrowaczewski's masterful conducting of the Brahms Concerto, and the care, affection and insights he brought to Chopin's F minor Concerto.

Перевод

Следите за двумя из СССР и бразильцем-они будут победителями.

ФОРТ-УОРС Конкурс Вэна Клайберна достиг своей вершины ве чером в субботу.

Этот третий и последний этап конкурса трудным и приводящим в замешательство как исполнитей, так и слушателей.

...Я верю, что медалистами 1989 года будут Александр Штаркман и Алексеи Султанов из СССР и бразилец Кокарелли. Хотя мр. Кокарелли был кроток и мягок в сольных турах, произвел впечатление наиболее лиричными трактовками при исполнении камерной музыки, в субботу, во время исполнения 2-го Конверта продемонстрировал высокий лиризм и глубину чувств,

Мы также слушали его в Первом концерте Брамса, это было монотонно-ритмично, идеально в плане виртуозности , почти превосходно, Но это не трогало , не "освещало". Но это было очень профессионально. Он легко превзошел мр.Люпо, игравшего концерты Шопена и Рахманинова. Покинут ли они шестерку финалистов? Об этом можно гадать, но я предчувствую,что первый приз достанется Штаркману, второй -Султанову и третий -Кокарелли. Но - возможны другие сценарии.

Например, первый приз может получить Султанов, а второй -Штаркман. Возможен и вариант, что Кокарелли и Султанов разделят второе место, или даже - оба русских поделят первый приз. Я не вижу Кокарелли претендентом на первое место,но...

Joрn Ardoin

The

Winner will have it all — and more

By John Ardoin

.FORT WORTH — What makes a winner? That question must be uppermost in the minds of audience members who have sat so patiently and attentively during the preliminaries of the eighth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. How do you separate one accomplished performer from another, all of whom must appear worthy of some sort of prize?

The answer lies not just in technique, tone, musicianship, nerve or any of the other ingredients essential to enter and survive a harrowing experience such as this. To win, you must have may 27 — june 11 every good thing every other competitor has in greater abundance, plus something more, something of your own that excites the imagination and raises goose bumps.

In short, you must have what the Soviet Union's Alexander Shtarkman had Tuesday and what his countryman Aleksei Sultanov and

demonstrated Wednesday during the final preliminary

round. The real contest has narrowed down to these three amazing artists. Any one of them would provoke excitement in a competition; having all three at the Van Cliburn is creating bedlam. For his second appearance, Mr. Sultanov left his critics open-mouthed with his playing of the slow movement of Mozart's Sonata K.

He clinched his remarkable second appearance with two movements of Prokofiev's Seventh Sonata, played with audacity, wizardry, artistry and animal vitality. He seems to stretch himself and get better each round. Again it fell to Mr. Burmester to follow in the wake of Hurricane Aleksei, and again he triumphed in his own special way. He opened with the Mozart Sonata K.

The final day of preliminaries had begun strongly with the return of

Young Soviet emerges as Cliburn standout

By John Ardoin

In every competition, yon wait for the contestant who takes absolute command of the stage and the instrument, a competitor possessed by the music he or she has chosen to perform. That moment in the eighth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition came Monday corning with Aleksei Sultanov from the

Only 19, Mr. Sultanov is that sort of inspired per-former who establishes standards by which other players must be held accountable. He Is a pianist who doesn't need to be crowned a winner; his playing boldly proclaims it

His preliminary trial peaked with an iridescent, intensely lyrical tracing of Chopin's second Scherzo, and he unleashed a torrent of passion and sound In etudes by Chopin and Rachmaninoff.

He seemed an impossible act to follow, but the wonder of Monday morning was that the next pianist was capable of holding his own in a very personal way.

Portugal's Pedro Burmester used his liquid, extremely flexible and variegated sound to rich effect In a superb, searching performance of the toccata from Bach's Sixth Partita: it was the most magical playing of Bach in the preliminaries. His Haydn had whimsy and grace, and to it be added the unexpected element of mystery.

Chopin's Impromptu. Op. 36 and Scriabin’s Etude in D flat followed, with the Chopin free and spontaneous and the Scriabin lilting rather than driven. The latter piece works both ways; I happen to prefer Mr. Burmester’s style.

Of particular Interest — again during the morning session — was

While the afternoon session — the end of the first phase of the preliminaries — bad occasional highlights, it was a largely an uneventful period until

Miss Suh brought clarity to Bach's "Italian" Concerto, enormous drama to Beethoven's Op. 7 Sonata and took Chopin's first Scherzo at a brilliant dip. which never faltered. But It was in the Liszt Paganini Etude with which she ended her group that the heavens opened, and she made a shining bid for a place In the Cliburn sun.

Commissioned work gets varied treatment

By John Ardoin

FORT WORTH — No one 1$ certain of the origins of what has come to be known as "the contest piece" — a commissioned work required of all competitors in a music competition. But it is now a fixture at most contests, and it has always been a part of the Van Cliburn International Piano competition. The Cliburn has commissioned such of composers as Aaron Copland. Samuel Barber. Leonard Bernstein and John Corigiano for contest pieces, and this year's work is by William Schuman. It is a set of variations titled -

The Schumon is no better and no worse than most, and certainly core Untenable than easy, given I’ts rather folksy, straightforward character. But so far It has not fared well In the Cliburn.

During the first day of the semifinals. It was treated either with disdain or with indifference. Finally on Saturday cane a suave and convincing performance by

Mr. Sultanov placed the Schuman between two eighty keyboard works — Beethoven’s "Appassionata" and Chopin Third Sonata. Both were given extraordinary' performances In Mr. Sultanov hands the Beethoven became as much a feat of control and concentration as one of pianism. It was a grand musical experience as well as a mesmerizing theatrical one, and it again marked Mr. Sultanov as the most compelling and dominant artist In these proceedings. His Chopin was equally exciting and individual — perhaps too individual for some. Bui then, what arc mannerisms to one person are Insights to another.

The balance of Mr. Cocarelli’s recital included an airy, charming performance of Schumann "Abegg" Variations and a trying and inadequate one of Brahms Sonata in К Minor.

Saturday's first recital was given by

His gifts are great, but still In a formative stage, for his playing often was without sufficient definition; as If it lacked an inner core. For all his sensitivity, his playing Is at ticics subdued to the point of being overly self-effacing.

In the chamber music category, Saturday's best were the solid, professional, but hardly eventful performances of the Brahms Quintet by America's Kevin Kenner and of the Schumann Quintet by Portugal Pedro Burmester. Both appeared with the

Music Review

Pianist Sultanov: A Conquering Winner

Less than two weeks after winning the eighth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in Ft Worth,

And, unlike the last three Cliburn winners who began their post-competition tour with a first stop in Pasadena (in 1977, 1981 and 1985) and later returned with disappointing results, Sultanov conquered immediately — and unequivocally.

More important than his musical and technic 1 credentials — which seem perfectly in order and even surpass in some respects the standard we have come to expect from international competitors — is Sultanov's personality.

He has one. It seems individual, perhaps even unique. And the impassioned articulate and sensitive playing that flows from his arms and fingers with the naturalness of a lion's roar or a bird's cooing expresses something more — much more — than mere good training, as cherishable a quality as that may be. It expresses a successful bonding between performer and listener.

Playing an old-fashioned (some might even say hackneyed) debut program consisting of well-worn sonatas by Mozart, Beethoven and Prokofiev and too-common show-pieces by Chopin and Liszt, Sultanov distinguished himself in every way. And won hearts in the process.

He probed familiar works with a bright but never perverse imagination. He reinstated appropriately the conversational flow of musical sentences most of his listeners could recite by themselves. And he heated up these chestnuts to their full flavor.

Beethoven's "Appassionata" Sonata became a celebration — and not for a moment a cerebration — of direct communication from pianist to audience. Sultanov gave it the full range of his dynamic interests, caressed the inner workings of the great slow movement, then rode the finale to a glory to which many aspire but few achieve.

In a very few moments, his Mozart — the Sonata in С, K. 330 —- went beyond the limits of style and restraint. But, in general, it purled along, made sense as music, and stayed in its own century Prokofiev's sure-fire Seventh Sonata seemed. after the fact, a tad contrived — Sultanov may by now have earned the right to be tired of it yet it emerged as predictably effective and hair-raising as any reiteration of it we have heard in this locale.

The compact, tireless pianist seemed most at home in the display mode of Chopin's В - flat minor Scherzo and Liszt's "Mephisto" Waltz, where his accuracy, speed and passionate delivery gave them a surprising freshness. In an evening of quick responses and hyperactive tempos, Sultanov saved the fastest for last. His two encores were both by Chopin, the "Grand Valse Brillante" in E-flat and the ''Revolutionary''.

By Daniel Cariaga,

Times Music Writer

Saturday , June 24, 1989

The Russians

Seven Cliburn contestants carry on the intimidating tradition

At the breezy garden party nothing seemed to faze Lin Hai, the tall, impassive young Chinese pianist. Not the

Fort Worth Star-Telegram / Monday, May 29,1989

Stage set for Cliburn competition

The 8th Van Cliburn

Now, the fate of the eighth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition rests in the well-rehearsed hands of 38 of the world's most promising young musicians.

The first chords will resound at 9:30 a.m. Saturday, once American David Buechner takes the stage at Ed Landreth Auditorium at

During the last Cliburn competition in 1985, Mr. Buechner was an early favorite among both the audience and the media; his failure to advance to the semifinals brought a public outcry. He is at the cutoff age for the Cliburn; this is his last chance at the competition.

The taciturn Mr. Buechner — so far, he has refused to talk with reporters — already has emerged as one of the high-profile competitors. Others seem destined to be closely watched for reasons besides contro versy.

Karoly Mocsari, a 27-year-old Hungarian who now studies in

"I have to reach the finals," he said.

West German Jurgen Jakob said there is such a thing as too much practicing before a competition. "It's like in sports," said the 27-year-old who has recorded and performed extensively in his country. "You can't run

During this week, each musician was given an hour to select one piano out of eight to play during the competition. There also was time for photographs, interviews and parties, including a lawn party Thursday night where competitors drew numbers to determine the order in which they would perform.

After more than 45 hours' worth of preliminary performances, 12 pianists will advance to the semifinals, June 2-6. Then six will compete in the finals, June 8-11. The 14 judges will announce the winner on June 11.

First prize is a $15,000 in cash

and a worldwide tour that could earn the performer up to $200,000.

All the competitors are keenly aware of what a victory would do for their careers. have to get one step closer to the top."

The Soviets will be getting most of the attention, if only because this is the first time they have competed in the Cliburn since 1977. Of the five in the field, Aleksei Sultanov is the Wunderkind. Program information lists his age as 20; he says he is 19, and he looks even younger.

Three years ago, Mr. Sultanov competed with a broken finger in the Tchaikovsky Competition in

To Mr. Sultanov, the Cliburn holds special meaning because of its namesake, who is planning a So viet tour this summer. The young Russian spoke of the

"He's a brilliant pianist," Mr. Sultanov said through an interpreter. "The Russians miss him very much. He has a Russian soul."

By Wednesday, all 38 competitors had arrived in

The pianists all are staying with

And practice is what the competitors have been doing with most of their spare time.

By Nancy Kruh

The

Saturday, May 27, 1989

Dealings ease with Soviets over Cliburn Under Gorbachev's new policies,

the U.S.S.R. offered to let the competition pick any qualified pianist, whether officially sanctioned or not.

Glasnost has reached the banks of the slowly flowing Trinity.

Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev's policy of openness not only permitted the current exhibition of unofficial Soviet art at

That's not to say that the Cliburn selection process was exactly the same as else where or that Soviet cultural authorities harbored no suspicions that the choices they pushed for might be deliberately sabotaged.

Of 193 applicants who auditioned on three continents, five were Soviets pre-screened by Gosconcert,

But for the first time, Gosconcert officials said that if the Cliburn heard of any other qualified Soviet pianist, he or she would be allowed to compete in Fort Worth — though without the Soviets picking up the tab for air fare, said Richard Rodzinski, the Cliburn's executive director.

"This time we could have gone beyond their pool," he told an informal

Since the Cliburn this time could have rejected or chosen any of the five proposed, there were initial Soviet apprehensions that it might purposely choose those least likely to succeed, Rodzinski recalled. This led to hesitance in allowing the audition to be videotaped for the screening committee based in

" 'What would happen if you didn't select those whom we consider the top three?'" he quoted the Soviets as asking him.

The U.S.-bom, European-reared Rodzinski, a persuasive former artistic administrator of the Metropolitan Opera, said he argued that it was • in the interest of the Cliburn as an international competition to locate the best talent available.

"It's easy to choose the top three," Rodzinski said he told them. "And furthermore, if we don't find any more better in

The videotaping went ahead.

In the end, the committee in

Although such pre-screening was not conducted in

"When it is impartially done, it saves us a lot of work because they filter the best," he said.

Cliburn officials are confident the Chinese and Soviets handled it objectively, he said, "because of the fact that they were willing to let us hear anybody else. I think that's a very clear indication they were really trying to do their best."

It will be the first time since 1977 that any

Soviet citizen will be competing in the Cliburn. There were none at the last two competitions because bilateral cultural ties had been snapped with the 1979 Soviet invasion of

"The fact that they were not participating all these years was traumatic for young Soviet pianists, I am absolutely sure," said Alexander Toradze, 36, who won the silver in the 1977 Cliburn and defected three years later. "Many youngsters would like to see their careers and musical life going the way our careers and lives took us.

"Now, after a long dark winter, spring has arrived."

The ascension of the reform-minded Gorbachev, the introduction of glasnost and the withdrawal of troops from

For example, the Cliburn requested

the personal mailing addresses of the Soviet competitors. Past programs were only able to list them "c/o Gosconcert,

Permission was granted this time, but the information arrived after the printer's deadline. Rodzinski said he's thinking of a way to insert the information — by hand if necessary.

Toradze said the package of concessions the Soviet authorities granted the Cliburn should not be underestimated.

"I see it as a big change, a major change and a happy one," he said in a telephone interview from

And if any international competition could wrest such concessions, it would be one associated with

"His name represents ultimate fairness," Toradze said. "Van Cliburn is a sacred name in the

he represents, his victory in the (1958) Tchaikovsky Competition was a unique celebration of art triumphing over mistrust, over the Cold War, over politics."

Toradze attributed to glasnost the fact that Soviet competitors will participate even though a Soviet defector, conductor Maxim Shostakovich, is a member of this Cliburn jury. The Soviet Georgian-born pianist said he doubted if any would have been sent under such circumstances before the Gorbachev era.

"" Toradze contrasted the current, open climate with that of 12 years ago when he and other Soviet competitors were ordered not to contact Youri Egorov, an entry who had defected to the West in 1976.

The stock (if the Kremlin thought in such terms) of the Soviet juror at the 1977 Cliburn, a man named Nikolai Petrov, shot up in Moscow not because Toradze won the silver medal but because "Egorov was eliminated before the finals," Toradze asserted.

"Politically, that was more important for the Russians."

Many, including Toradze, said they believe Petrov's influence on jurors played a role in Egorov's poor showing. But Rodzinski said, "I don't think it'll be ever possible to find out all the truth."

Toradze said he expected Soviet competitors would be allowed for the first time to mix freely with the others, including three Americans of Soviet

origin.

In 1977, Soviet pianists had to check in regularly with their "translator," whom they were convinced was a KGB agent, albeit a highly sophisticated one, he said.

"We telephoned her even when we went out for a hamburger," he said.

"The attitude of Soviet competitors this time will be more human, more normal, more collegial because they will be less fearing the eyes of the other

Soviets — like the fake translator who will be watching and monitoring all their movements," he said.

"But I don't know if they will take chances, use this opportunity, be willing to be open.

"Freedom has to be learned. It's a different alphabet, a different language and you have to learn it. But because it is a natural language for humans, once you get the smell of it, it's a universal process."

By Barry Shlachter

Fort Worth Star-Telegram

Thursday A.M., May 25, 1989